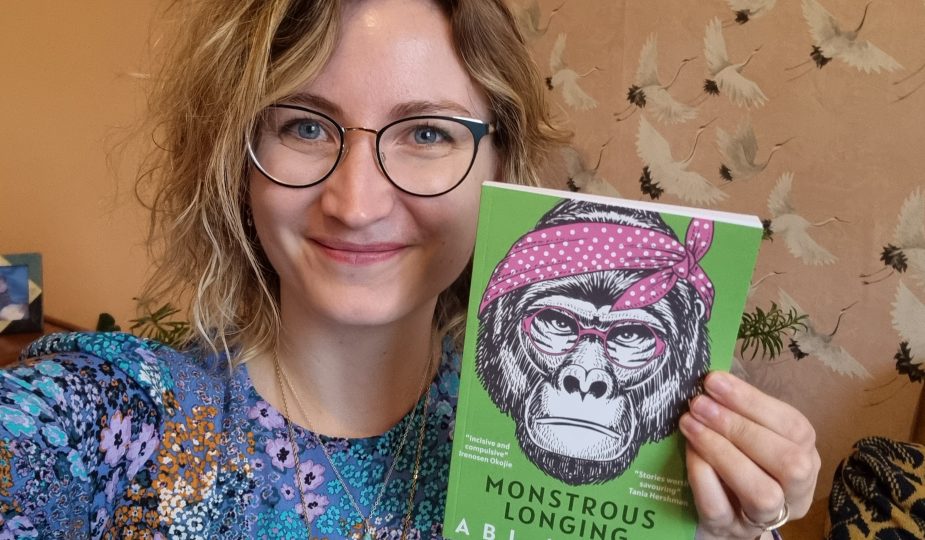

Every year Dahlia Books hosts students from the University of Leicester for a 10-week placement. Students are given tasks from a range of the different sectors within publishing to give them a thorough understanding of the industry from the perspective of a small press. This scheme enhances the learning of students and allows them to learn and develop some key skills. As part of their placement this year students Aiysha Bux and Saarah Ismail worked on Abi Hynes’ upcoming short story collection, Monstrous Longing. For this blog, they interview Abi about her book.

Abi Hynes is an award-winning fiction and drama writer from Manchester, who transfers her literary wisdom in the variety of writing workshops she runs. When Abi is not writing, she works as the head of publishing at IPPR, a progressive think tank based in London. Abi has recently penned the short story collection, Monstrous Longing, which features a range of captivating and original stories. We spoke with Abi to learn more about the voice behind the words…

If you had to, how would you define this short story collection in one sentence?

I think it’s a collection about people – mostly women, mostly human – who want things they are not supposed to want, in ways they’re not supposed to want them.

Can you tell us a bit about the process of how these short stories all came together to form a collection?

With the exception of the title story, I didn’t write any of these pieces with the idea of a collection in mind. I owe the vast majority of them in some way or another to Manchester’s incredible live literature scene.

Over the past 12 years or so, that scene has nourished and nurtured me as I’ve gradually created a body of work, the darkest and most horror-tinged of which you can find in Monstrous Longing. These stories were often written for performance, either for open mic slots or – later – paid commissions. Mr Thornton’s Mother was written for a Bad Language event as part of Museums at Night; Long Distance (stars and stars) was written for a Flim Nite event as a commissioned response to the Bruce Willis sci-fi film The Fifth Element; and The Savage Chapel, my most successful story to date (it won the Cambridge Short Story Prize in 2020) was first written because the brilliant David Gaffney commissioned me and five other writers to tell stories inspired by Macclesfield at an event for Macclesfield Literature Festival. As I wrote, I began to submit to magazines and journals, and eventually my work started to get published.

It was sometime around the start of the pandemic that I really started to think about putting some of my stories together as a collection. I tried grouping them in a few different ways: there was a much lighter version of this book for a while that I was calling Words for Love, and at one point it was going to be a mini pamphlet of purely science fiction stories. But the version of this book that I finally found the courage to send to Farhana at Dahlia Publishing has got nearly all of the messiest, most personal, and hardest-to-write pieces I’ve ever penned in it.

You mainly write screenplays, why do you choose to also write short stories?

I have a very practical answer to that question, and a much artsier one.

The practical answer is that being a drama writer is really hard, and I need a break from it sometimes. The wonderful and awful thing about writing for stage, screen or audio drama is that by definition you need a lot of other people to get involved, and you therefore spend a huge amount of time waiting for them to email you back. Having fiction to return to when I need some imaginative time by myself, to remind me what really matters to me, on my own, with only the page in front of me, helps keep me sane. Plus the rhythm of submitting shorter work to journals and magazines, those little spikes of joy when something gets accepted and finds some readers – that is a truly lovely thing.

The artsy answer is that the process of writing short stories is incredibly special. It’s a craft that asks for immersion rather than stamina; you can write a short story in a lunch break, or on a beach, or on a train. It doesn’t need a lot of time, it just requires you to show up and give it your undivided attention. That feeling of sinking into a new world for a brief but intense period is something I don’t want to give up.

What is your favourite form to write?

I definitely don’t have a favourite form – if I did, I’d probably just do that! I think what I like is variety. And switching from one form to another keeps me on my toes: if I notice that my prose isn’t as good as my dialogue because I’ve spent months writing only scripts, for instance, it gives me a nudge to keep working on it.

What is your favourite form to read?

I read more novels than anything else, and I think that’s partly because it’s the one form that I allow myself to read purely for pleasure. I’m in a very long historical fiction phase at the moment, and totally enamoured with my lovely local library that means I can read all the latest releases without filling my house with enormous hardbacks.

I understand that you also work as an editor, what’s it like to be on the flip side of that process, having your own work edited as an editor yourself?

I like to err on the side of generosity, whether I’m editing or being edited. I think the best editors, like Farhana Shaikh who edited this collection, are curious without meddling. Their job is mostly to ask questions, to find the root of what you’re trying to write about and help you make it the best version of that vision that you’re capable of.

I like being edited, because I think somebody paying close attention to your writing in order to help you make it better always feels like such a compliment. I think writing drama has taught me to value an outside eye perhaps more than a lot of fiction writers generally do: even if I don’t have a professional editor, I would never send a piece of work out into the world without asking several trusted readers to take a look at it first. I think I’m mostly good at taking criticism, and I’m certainly not precious about my writing: if notes will make it better in the long run, then I want the notes.

The only thing I don’t take kindly to is suggestions, especially not for lines of dialogue. I think you can tell a Frankenstein piece of writing a mile off – if you start sticking in someone else’s voice and rhythm and energy, the whole thing can turn quickly into word soup. As an editor, I know that I have limits: I haven’t thought about the piece as deeply or for as long as the writer has, so I’m not about to start trying to trample on what they’ve made with my own choices.

So yeah, if you give me a line the way you would’ve written it, I’ll smile and nod, but there’s no chance in hell it’s going in there.

Reading this collection, I found myself trying to connect the stories by theme – is there any one particular inspiration behind the collection, or is there an inspiration behind each story?

There definitely was no one single starting point, because some of these stories were written over a decade apart: Silt was written about 12 years before the title story, Monstrous Longing. But there’s a lot in there about love, particularly parental love, I realise. There’s a lot of hunger, too, and desire, and greed, and shame – shame perhaps most of all. I think this is because I often start a story to try and unriddle an emotion I’m experiencing that is uncomfortable or that I don’t quite understand. Putting it on the page is my way of making it keep still so that I can take a clearer look at it.

I’m not an autobiographical writer, but the one piece of creative non-fiction in here, Phantasmagoria, is very evidently inspired by my experiences as a drama student at university, and the moments leading up to my decision – or perhaps just realisation – that I wasn’t going to become an actor like I’d always planned to. That’s the most nerve-wracking story I’ve ever published, but doing so took the sting out of some bruises I’d been nurturing for a really long time…

Is there anyone you look up to for inspiration when writing/ do you have any literary idols?

So many! For short stories, I’ve been hugely inspired by Carmen Maria Machado, George Saunders, Angela Carter, Shirley Jackson, Daphne du Maurier and Ursula Le Guin. My friend Tania Hershman – her work and her workshops, which I’ve been privileged to take part in – is also an endless source of inspiration.

Hilary Mantel is probably the closest to what I would call an idol. The world is richer and wiser because she lived and wrote in it.

I thought ‘Customer Reviews for Ashley Wiccan’s WonderLust Love Potion’ is one of the most original short stories I’ve come across, what gave you the idea for this?

Thank you! (I think.) That story started as another Flim Nite commission. Those guys had the brilliant idea to commission writers and performers of all kinds to ‘retell’ cult classic films through whatever media they chose. It made for such weird and wonderful evenings, and I was especially delighted when they invited me to take part in their event inspired by that amazing witchy teen horror film The Craft, which my sister and I used to have an obsession with that was bordering on religious.

Out of all your works, which are you most proud of?

That is a terrifying question, but of all the stories in this collection I suppose I have a soft spot for The Savage Chapel. That story was immensely hard to write: I was trying to distill all these enormous ideas into something really quite tiny, and I was determined not to shrink my ambition for it just to squeeze it into a smaller shape. I think it was so difficult because the issue I was wrestling with at the heart of the story was a big one. I was struggling, as I have often struggled, with the conflict between religious faith and the harm that religion has done and continues to do to my LGBT+ community. I wanted to find a loving way to reach across that gulf, and the way I found was this: that there are, and always have been, gay people of faith. Our exclusion from places of worship – the fact that so many of them will not let us marry there, for example – is deeply wrong and it makes me furious. But the people it hurts most are those within those faiths; by imagining them, I wanted to take that anger and turn it into love.

When the story finally emerged in its final form it felt like a magic trick; by some alchemy, my slogging away at it (it really was hard work) had turned it into something more elegant and eloquent than I’d dared to hope I was going to be able to achieve. Some stories arrive almost fully-formed, and this was definitely not one of those! I think I’m extra proud of it because its success was hard-won and required so many hours of struggle.

If you had to choose a top five list of books to recommend, what would they be?

Can they be anything? If so I’m going with Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body & Other Parties, Philip Pullman’s Northern Lights, Maggie Shipstead’s Great Circle, and Jane Austen’s Persuasion.

What do you want to achieve as a writer?

Oh god, that’s a big question! Lots of things, and different things depending on the project. In this collection, I’d like to tell the truth about some feelings that are big and dark and awkward, but that I think most of us experience. I think I always want that ring of authenticity: that sense that I’m not faking anything, I’m not fudging it, I’m telling you something honest. Most of us live lives that ask us to spend a lot of time pretending, and I think I’m always looking to find a way to drag some of the stuff we have to sweep under the rug out into the light.

How would you advise a young writer who aspires to publish their stories one day?

Keep writing! Get submitting, too – there are so many wonderful publications out there taking unsolicited submissions, and gently building up a publication record is an excellent way to boost your confidence, your credibility, and to learn what works and what doesn’t. Start a spreadsheet, so you can keep track of everything. Treat it like a game: I know lots of writers who aim for 100 rejections a year (and that way, you’ll probably end up with a few acceptances, too). But don’t throw your stuff out too randomly; instead, find other writers whose work you like, look up where they’ve been published, and submit to those places.

Join a writing group, or form one. Sign up for a class or a course or a workshop. Get over that hurdle of sharing your work with people, and start figuring out whose opinions you trust and whose tastes you share. Join a library. Read widely, and especially new books: the classics are great and they can inspire you, but they’re not going to teach you how to write for contemporary readers. Don’t be that guy who says he ‘doesn’t like modern cinema’ while trying to make it in modern cinema.

You only learn by doing. Writing is a never-ending apprenticeship. Off you go.